The sfifa’s history and cultural significance

The sfifa is a form of passementerie integral to the aesthetics and rich material symbolism of traditional regional clothing styles, traditional saddlers, ritual and decorative objects in Morocco. It’s both a traditional craft with roots in antiquity and a thriving form of contemporary artisanal creativity.

The sfifa is made by card-weaving narrow lengths of fabric used as decoration and trimmings (including borders, trims and belts) on caftans and djellabas, traditional saddlers, and decorative objects. The sfifa has also traditionally been used to make the headdress for Amazigh and Jewish Moroccan brides.

There exists very little documentation of the history and techniques of sfifa weaving, despite its integral importance to the symbolic ornamentation and regional diversity of Moroccan dress.

The TIMENDOTES Association’s vision and goal is centered on nurturing artisanal skill and sustaining sfifaweaving in Morocco. In addition, cutting-edge historical research and documentation will be vital to recognizing the sfifa‘s significance in contemporary craft and dress practices.

Card-weaving in North Africa

Whilst there is very little documentation around the origins of card weaving in Morocco, there are specific techniques and style parallels that afford analysis and credible speculation on its development and influences across centuries. These are ripe for further research, and one of the goals of The TIMENDOTES Association is to bring together practitioners and academics to strengthen knowledge of the sfifa since it represents a vital aspect of Morocco’s cultural heritage and material culture.

The anthropologist and folklorist Arnold Van Gennep (1873-1957) first became interested in this technique after reading an illustrated article by German textile expert Margarethe Lehmann-Filhès on cardboard weaving in Iceland published in 1899. Van Gennep was so inspired that he learned the technique and continued to devote himself to it. Lehmann-Filhès seminal book Über Brettchenweberei (German-About Tablet Weaving) was published in 1901. Still, despite Über Brettchenweberei’s wide-ranging scope and profound erudition, Van Gennep found that North Africa was not mentioned at all. He felt it vital to look more deeply into the extant practices of card weaving in North Africa.

When Van Gennep conducted his ethnographic fieldwork on card weaving in Algeria between 1910-1911, an old man from Tlemcen told him that, in n the time of the Turks [from the 16th century until 1830, northern Algeria was part of the Ottoman empire] everyone wove with cards in Algiers but that all the looms had been burnt down a long time ago. Moreover, Van Gennep discovered that two of the card weavers interviewed in Tlemcen had learnt the trade in Tetouan and the other in Tlemcen itself, from a Jewish weaver originally from Marrakech.

We note that the Algerians themselves learned card weaving in Morocco and from Jewish weavers of Moroccan origin in Tlemcen.

From the testimonies collected from Algerian card weavers in 1910-11, Van Gennep learned that the technique had been used in the past in Blidah, Tetouan, Tlemcen, Marrakech and Oujda, but had disappeared from these cities. He was told that it was still in use in Fes at the time.

Synergies between sfifa and medieval Passementerie: Morocco as red link to all countries of the Mediterranean

Another cross-cutting flow is rooted in the history of the Moroccan Jewish community. Following the Spanish Inquisition, Spain expelled Jewish citizens as part of the Alhambra Decree in 1492, and many fled to North Africa. The Jewish community in Morocco particularly specialized in silk work, from the rearing of cocoons to weaving. They also had a virtual monopoly on the manufacture of gold thread and its use in textiles and embroideries.

The practice of weaving sfifa with real gold was associated with the Jewish community in the mellah of Fes, and numerous examples of lavishly decorated Moroccan bridal dress adorned with gold woven sfifa can be found in museums worldwide. Fes’s Jewish citizens were particularly active in silk work, and the production of trimmings was also their specialty. Mulberry trees were numerous in the north of Morocco, and the Jewish community raised silkworms. Once the cocoons had been reeled, the silk was dyed in bright colors and then wound onto reels to be sold throughout the country. Foreign imports, however, put an end to local production.

To embellish and make the trimmings more bright and refined, Jewish craftsmen made and used « golden thread », called scalli in Arabic. It was obtained by winding a thin, narrow strip of golden silver onto a twisted silk thread. The production required the intervention of several highly specialized workers, and more than three-hundred families lived from it in Fes. This industry continued until 1929 when an owner brought from France a machine to wind the blade and the silk. Almost all of the gold thread workers found themselves out of work overnight.

One can speculate whether Jewish artisans would have brought their own knowledge of wrapping fine threads in precious metals from Medieval Europe, where many examples of ecclesiastical vestments decorated with card-woven bands incorporating precious metals are known to have existed.

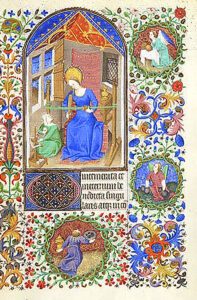

There are numerous illuminated manuscripts from Europe that show weavers using a similar method of warp tensioning (stretching the yarn between two poles) that are used in Morocco. The earliest direct evidence of these similar methods of warp tensioning can be found in Book of Hours from the 15th century, with depictions of the Virgin Mary occupied in card weaving.

Although the lack of documentation means that we can often only speculate as to the historical threads of influence and cross-cultural exchange, there remains little doubt that Morocco’s rich history and geographic location situated between the Mediterranean and Northern Africa placed it at the axial point of flows of goods and ideas that textiles like the sfifa embody today.

The Virgin Mary, decorated nimbus, is seated on a chair at a loom. The loom is remarkably similar to those used to card weave sfifa in Morocco and points towards possible entwined histories through the migration of Jewish communities from Spain to Morocco in the 15 century.

Book of Hours. France, Paris, ca. 1425-1430. MS M.453 fol. 24r. The Morgan Library and Museum.

The sfifa as part of Amazigh and Jewish cultural symbolism

The sfifa is an intrinsic part of traditional Moroccan dress, adorning caftans and djellabas, with especially ornate decoration for ceremonial occasions.

Both the Amazigh and Jewish communities in Morocco use sfifa as an integral and important part of customary dress for brides on their wedding day. In Amazigh communities, the bride wears a headpiece known as izar, in which an intricate, geometrically patterned sfifa is placed on her head and covered with a veil that drapes down over the shoulders.

In Moroccan Jewish communities, the bride’s head is adorned with a sfifa decorated with many hundreds of pearls and sometimes rubies to form a splendid diadem or tiara.

This exquisite bridal diadem worn by a Jewish bride uses sfifa, pearls and pieces of gold jewellery with semi precious stones on silk.

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Indeed, the sfifa formed an integral part of Jewish dress and craft livelihoods after Jewish individuals were expelled from Spain in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs. Many crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and sought the protection of the Sultan of Morocco, who at the time ruled from his court in Fes. Jewish communities already living in North Africa were now joined by Sephardi Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who brought with them customs and traditions developed over many centuries.

The Sephardi Berberisca Dress (Arabic keswa el kbira) worn on the henna night of the bride, has roots in the Iberian Peninsula, and was first produced by Jewish embroiderers of the Spanish Royal Court in the Middle Ages. The keswa el kbira is composed of several garments, and the sfifa plays an important role in the ornament and symbolism of these pieces. The zeltita (skirt) is often adorned with twenty-two braided galloons (sfifa) as a reminder of the twenty-two letters in the Hebrew alphabet and as a metaphor for the Torah. Another characteristic number in which the sfifa galloons can be found is twenty-six, highly significant in Judaism since according to the gematria this is the numerical value of the name of God.

It’s thought that the widest band at the bottom of the skirt originates from Europe. In France, this type of braid is called system braid; it is a metallic braid whose decoration is only visible on one side, to save the precious material. In fashion in the 17th century, it was used to underline or hide the seams of the various pieces that made up Christian liturgical vestments. The system braid used on zeltita is often woven with decorative grapes and vines symbolic of prosperity and good fortune in Judaism.

The zeltita, as part of the keswa el kbira ensemble, represents a fascinating confluence of Sephardic Jewish traditions with Moroccan culture and craft. The silk threads were painstakingly covered with a layer of gold foil, a craft that was a specialty of Jewish artisans in Fes, and the Jewish community of Fes are known to have been central to the production of gold woven sfifa.

The front of the keswa el kbira from Tetouan typically features two symmetrical pairs of large spirals decorating each side of the gombaiz, with alternate braided gold thread and gold cord. The spirals symbolize the cycle of life and eternity. In an example shown here, golden sfifa are used for the spirals on the gombaiz. The decline of the silk industry as a whole, as well as the emigration of Moroccan Jews in the 1960s to Israel, meant the production of handwoven gold thread sfifa for the keswa el kbira ceased.

This beautiful Keswa El Kbira (Arabic-Great Dress) worn by the bride is ornamented with brands of sfifa that form highly significant shapes and numbers in terms of Judaic religious symbolism.

The Center of Judeo-Moroccan Culture (CCJM), Brussels.

L’habit traditionnel marocain et la sfifa

Indeed, the sfifa formed an integral part of Jewish dress and craft livelihoods after Jewish individuals were expelled from Spain in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs. Many crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and sought the protection of the Sultan of Morocco, who at the time ruled from his court in Fes. Jewish communities already living in North Africa were now joined by Sephardi Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who brought with them customs and traditions developed over many centuries.

The Sephardi Berberisca Dress (Arabic keswa el kbira) worn on the henna night of the bride, has roots in the Iberian Peninsula, and was first produced by Jewish embroiderers of the Spanish Royal Court in the Middle Ages. The keswa el kbira is composed of several garments, and the sfifa plays an important role in the ornament and symbolism of these pieces. The zeltita (skirt) is often adorned with twenty-two braided galloons (sfifa) as a reminder of the twenty-two letters in the Hebrew alphabet and as a metaphor for the Torah. Another characteristic number in which the sfifa galloons can be found is twenty-six, highly significant in Judaism since according to the gematria this is the numerical value of the name of God.

It’s thought that the widest band at the bottom of the skirt originates from Europe. In France, this type of braid is called system braid; it is a metallic braid whose decoration is only visible on one side, to save the precious material. In fashion in the 17th century, it was used to underline or hide the seams of the various pieces that made up Christian liturgical vestments. The system braid used on zeltita is often woven with decorative grapes and vines symbolic of prosperity and good fortune in Judaism.

The zeltita, as part of the keswa el kbira ensemble, represents a fascinating confluence of Sephardic Jewish traditions with Moroccan culture and craft. The silk threads were painstakingly covered with a layer of gold foil, a craft that was a specialty of Jewish artisans in Fes, and the Jewish community of Fes are known to have been central to the production of gold woven sfifa.

The front of the keswa el kbira from Tetouan typically features two symmetrical pairs of large spirals decorating each side of the gombaiz, with alternate braided gold thread and gold cord. The spirals symbolize the cycle of life and eternity. In an example shown here, golden sfifa are used for the spirals on the gombaiz. The decline of the silk industry as a whole, as well as the emigration of Moroccan Jews in the 1960s to Israel, meant the production of handwoven gold thread sfifa for the keswa el kbira ceased.

The ancient caftan of Tetouan is decorated with intricate embroidery and bands of sfifa forming decorative breastplates called Khanjar (dagger) after their knife-like shape.

Plate 15. Costume du Maroc (Costumes of Morocco), Jean Besancenot, 1942.

The sfifa and urban luxury consumption

Nadia Erzini writes off the consumption practices of the urban middle class in 19th-century Morocco. Given the lack of official European records of the local tastes and manufacturers of the time, Erzini uncovers Moroccan legal documents, such as marriage contracts, testaments, gifts and divisions of inheritance (dating from 1794-1894 and held in the Erzini archive). The documents reveal that three items were standard in marriage gifts (sdaqin Moroccan, marh in classical Arabic) in the marriage contracts of Tetouan throughout the 19th century.

By studying these contemporaneous legal documents, Erzini has uncovered detailed information that points to the importance of ornamented textiles during this era. There were strict rules as to what the groom should give the bride, and this must include a luxurious embroidered caftan. Erzini also uncovers evidence of the sheer value of ceremonial textiles relative to other property, for example in the legal documents for the division of inheritance of Ruqayya bint Ahmad Erzini (d.1863-4), one caftan mushajjar was valued at 1,600 mithqals- over five times the cost of a field outside the city of Tetouan (300 mithqals) and a quarter of the price of a new house (600 mithqals). Indeed a style of caftan made by the Bencherif family in Fes was colloquially known as khrib, meaning « the one who ruins » because this yellow brocade caftan embroidered with roses was extremely expensive.

One can extrapolate from this kind of historical information how important the indigenous silk weaving industry and its associated trades such as sfifa making have long been in Moroccan society.

The Caftan and Moroccan modernity: role of the sfifa?

What about the sfifa today? Since the mid-20th century machine made copies have infiltrated the market, severely impacting artisans who make hand woven sfifas. Today, it’s estimated that perhaps only two-hundred artisans who can still weave the sfifa remain across Morocco

Yet Moroccan dress such as the caftan has never been more popular, having undergone various reinventions and transformations since the start of the 20th century.

In 1912 The Treaty of Fes saw the creation of the French Protectorate. Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey, the first Resident General in Morocco, oversaw a flurry of activity around urban development and the preservation and revival of traditional crafts. For political, economic and aesthetic reasons, Lyautey insisted on separating Moroccan cities into European city centers (villas nouvelle) and Arab city centers (mdina). Moroccan fashion, such as the caftan, djellaba and takchita prevailed in the mdina and anticipated its role in creating a newly independent nation in 1956, where traditional dress has continued to play a central part in demarcating Moroccan identity and national pride.

In the 1930s Jean Besancenot documented traditional Moroccan dress and published Costumes du Maroc (Costumes of Morocco) in 1942, many of which offer tantalizing glimpses of the sfifa in the context of regional dress forms during this era.

Three consecutive monarchs from independence in 1956 onwards have made the caftan a key part of their different visions of nationalism, Muslim and Arab identity, and Moroccan modernity. His Majesty King Mohammed VI, may God assist him, belongs to the Alaouite dynasty and ascended to the throne in 1999. Since then, there has been a strong focus on political reforms and female emancipation, with many women’s craft co-operatives formed to enhance livelihood opportunities for women from poor, rural communities.

The contemporary context: heritage crafts meet new global markets

From the 1960s onwards Moroccan fashion absorbed and created hybrid styles as it both influenced international fashion and incorporated “Western” styles into its language.

French department stores like Galeries Lafayette and Le Bon Marche opened in the cosmopolitan center of Casablanca and provided the latest fashion trends from France. The flow of the international jet-set into urban centers such as Marrakesh and Casablanca saw designers like Yves Saint Laurent and Madame Gres incorporate caftans into their collections as part of a radical new spirit of freedom from French bourgeois convention. Following a visit to Morocco in the early 1960s, Vogue Editor Diana Vreeland published an article in Vogue 1966 titled « The Beautiful People in caftans” championing the caftan as fashionable.

In turn, Moroccan designers like Zina Guessous and Tamy Tazi reinvented the caftan, introducing elements of European fashion, making it lighter and more fitted to the body.

Since the 1990s, the growth of the formal fashion sector in Morocco has expanded the possibilities for expression through combinations of traditional and contemporary interpretations of Moroccan dress. The prominence of the Royal family in Morocco, who are regularly featured wearing caftans and jellabas in Moroccan lifestyle magazines, has added to the popularity of the sfifa as an integral part of Morocco’s cultural heritage and modern aspirations.

In all of this, the braided sfifa has remained intrinsic to Moroccan fashion, as important as the various forms of regional embroidery, yet mostly overlooked in both academic studies and museum collections. It is often both tantalizing yet frustrating how the sfifa remains just out of view in museum descriptions of Moroccan dress, textiles and regional embroidery styles. It is surely time that we pay more attention to the histories and skilled artisans who make the handwoven sfifa possible today.

The above photo shows a sumptuous Fes embroidery framed by golden sfifa.

This black velvet caftan typical of Fes and known as Caftan Ntaa is decorated with golden embroidery (Tarz Ntaa) and bands of golden sfifa, which demarcate its shape and lines.

Photo by M. Amine Dadda.